Sensibilities and Sensitivities in the Art of Rokeya Sultana

- Ranjan Kaul

- Jun 20, 2022

- 7 min read

by Ranjan Kaul

When Bangladesh won its hard-fought Independence in 1971, Rokeya Sultana was just about starting to paint. Having been a witness to those violent and turbulent times, her painful memories would keep returning to her and would get reflected in much of her art from time to time. It is indeed fitting therefore that her retrospective show is being held to mark 50 years of Bangladesh’s Independence and India-Bangladesh friendship. Organized by the Indian Council for Cultural Relations (ICCR) in collaboration with Bengal Foundation, the ongoing exhibition at Lalit Kala Akademi Art Gallery, New Delhi, titled by her name, “Rokeya Sultana”, comprises about 110 artworks and three animation video films. The exhibition will later travel to Kolkata in December under the auspices of the ICCR and will be replicated in Dhaka by the Bengal Foundation.

Gallery view, Rokeya Sultana’s exhibition at Lalit Kala Akademi, New Delhi (Photo by Aakshat Sinha)

At the opening of the show, Rokeya is on the extreme left in the front row (Photo by Aakshat Sinha)

Artist Rokeya Sultana at the opening (Photo courtesy of Bengal Foundation)

Born in Chittagong in 1958, Rokeya Sultana completed her graduation from Bangladesh College of Arts and Crafts in 1980 and moved to Santiniketan to complete her Master’s in Printmaking in 1983. The sensitive painter and printmaker and currently Chairperson of the Faculty of Fine Art, Dhaka University, Rokeya is known for her experiments with varied narratives, especially her explorations of themes related to womanhood and feminism and sensuality. The exhibition traces her trajectory from the time she worked in Santiniketan as a student under the tutelage of the Indian masters Somanth Hore, Sanat Kar and Lalu Prasad Shaw and later in Bangladesh under the mentorship of Saifiuddin Ahmed and Mohammad Kibria. The influence of these masters can be clearly seen in her early etchings and prints and her art in many ways embodies the shared art legacy of India and Bangladesh. However, the bold and restless artist that she is, Rokeya soon developed her own aesthetics and visual language based on her sensitivities, memories, and sensibilities through ceaseless exploration.

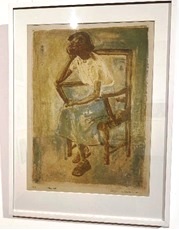

Left: Resting, Lithograph print, 1978; right: Man with Goat, Aquatint etching, 1983

(Photos from the exhibition by Ranjan Kaul)

Group of the artist’s works displayed on the gallery wall, showcasing her explorations and experiments with varied narratives

She experimented with simplified forms in her ‘Relations’ series with abstracted landscapes, while in the sequence of works titled ‘Earth, Water and Air’ she rendered abstracted interpretations of the Bangladeshi landscape and the world of nature interspersed with semblances of organic forms. However, it was when addressing issues of womanhood and concomitant complexities and the travails of motherhood in adverse situations, that she really came into her own, finding expression in her well-known Madonna series of the 1990s. Her artistic vision and continually expanding ouvre is thus a manifestation of the sensibilities of mother and child drawn from her own personal experience (as she explains, first as a daughter and then as a mother to her own daughter who now resides in Australia) intertwined with their relationship with nature – earth, water and air – as substitute, in a manner of speaking, for human relations.

Left: Relation, Tempera, 2003, 30” x 22”; Right: Relation 4, Tempera, 36”x 24”

Earth, Water, Air, Tempera, 1999, 48” x 48”

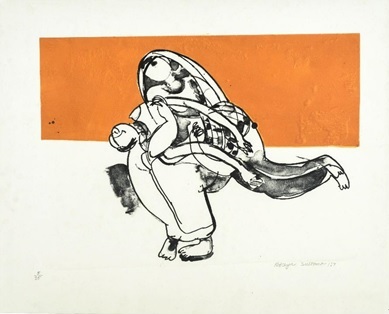

Named after Madonna, the legendary American pop singer-song writer who gained popularity in the 1980s and 1990s when Rokeya was painting, the artist's ‘Madonna’ series depicts the everyday woman navigating a complex world and challenging a patriarchal society. Her evocative work Madonna and the Passengers (1994) shows a mother with the daughter by her side inside a bus with her fellow passengers hanging onto the handrail desperately, swaying to the movement of the bus. Her memories of the Liberation War led her to revisit the mother-daughter theme with her monumental work, The Mother’s Pouch, which she painted in 2016. Rokeya tells me that her father worked with the police under the Pakistan government till he left the force to join the liberation army, leaving her mother to fend for herself and her. While the mother holds the rifle as their only safeguard, her daughter clutches their mere belongings in a pouch against the backdrop of dislocated refugees (reminiscent of the recent plight of migrant workers we saw owing to the pandemic in India) and the Mukti Bahini fighters.

Part of Madonna series

Madonna and the passengers, Soft-ground etching on zinc plate, 1994

Left: Madonna – Myth and Reality, Acrylic and tempera, 2009; Right: Madonna – Ma, Water colour on handmade paper, 2001

In 2010 Rokeya worked on a couple of powerful works in contrasting reds and white that are seemingly self-disparaging but are her sarcastic response to a patriarchal society. While in one she borrows imagery of a multi-breasted goddess (which can be seen in her earlier work in the Madonna series as well) with her head, resembling a goat, cut off and lying in the lap; in the other she uses a goat head (a recurring motif) with an inverted feminine form. As she explains, she was feeling low when she created these works – goats are generally regarded to be brainless, akin to how women feel when society gives neither respect or regard to them as possessing intelligence and ability equal to men.

Left: Untitled, Acrylic on canvas, 2010, 66” x 42”; Right: Obsession I, soft-ground aquatint, 22” x 14”, 2002

Untitled, Acrylic on canvas, 2010, 87” x 87”

Mother’s Pouch, Acrylic and tempera on Canvas, 165 cm x 336 cm, 2016

Her memories of the violent Liberation War remained firmly etched in her mind, much like her prints and she would revisit the turbulent times even after several years had lapsed, as can be seen in a haunting group of print works of killing fields, hanging ropes, corpses, dying women. While Birangona (the title awarded by the Government of Bangladesh to women raped during the Liberation War by the Pakistan Army and their local collaborators) is a touching depiction of the death of an unborn baby in the womb, Jagnnath Hall, on the night of March 25, rendered in contrasting black and white, is a painful and grim reminder of the dreadful black night of massacre in Dhaka University. Martyred Child is another moving work redolent of Michelangelo’s Pieta depicting Mary cradling the dead body of Jesus after he was removed from the cross.

Clockwise from top: Birangona /Women of War 1971, Lithograph print, 2017; Badhodhumi / Killing Fields 1971, Lithograph print, 2018; Badhobhumi /Killing Fields 2017, Lithograph print, 2017; Janani O Shaid Shontan / The Mother and the Martyred Child, Lithograph print, 2017; (Photos by Ranjan Kaul)

Around 2012, Rokeya began experimenting with a series of unique pressure prints which she christened ‘Fata Morgana’ (a mirage, seemingly unreal, and often derived from memory), where she used multiple cut-outs and impressions using varied surfaces, depicting the feminine form. Unlike her etchings and paintings, these pressure prints are neatly finished and painstakingly executed. The black-and-white works in the series have more of a graphic quality to them with well-defined boundaries, while her experiment using colour is freer and less deliberate, but to my eyes these cut-out prints seem to lack the emotive and expressive power of her other works. Perhaps she herself came to this realization because she does not seem to have returned to the medium and process.

Her recent highly imaginative and surreal series ‘Return the Innocent Earth’ are far more lyrical, fluid and layered, where she uses accidental effects and free-floating organic forms to revel in bountiful nature and the cycle of human life. Inspired by one of Tagore’s poems where the poet makes a plaintive plea to return the forest and take him back the city, Rokeya revisits her pet theme in the series – the undying relationship of mother-daughter with nature. In one work the imagery of the banana leaf is used as a metaphor of both providing a shelter as also a raft to navigate life’s journey; in the other the mother flies above as a guiding spirit, not wanting to leave the daughter feel alone, even as she is encouraged to find her own path. In the background is the ‘innocent earth’, the mangrove forests of Sundarbans – with water bodies, geese, flying angels, even a frog.

Group of Unique pressure prints at the display

Black-and white v. coloured Unique pressure prints, 2012

Return the Innocent Earth 1, Acrylic and tempera on canvas, 2021 (Photo by Ranjan Kaul)

Return the Innocent Earth 2, Acrylic and Tempera on Canvas, 2021, 79” x 82” (Photo by Ranjan Kaul)

Finally, I’d like to end with what I regard as one of the artist’s most successful works of the artist, Lost in the Maze of Hathirjheel, painted in 2020 after the Covid pandemic had abated somewhat.

Lost in the Maze of Hatirjheel, Acrylic on canvas, 2020, 54” x 108”

After being confined indoors owing to the pandemic, the mother-daughter duo stand on the bridge overlooking Hatirjheel in Dhaka, enjoying a breath of fresh air, feeling liberated and free. Another girl stands with her back to them, with vehicles moving in the background on the highway. A touch of the feminist streak not to be missed is the significant detail of the heeled shoe the young mother wears.

Enraptured by the above highly successful three works that are described above, Rokeya chose to experiment with a new, contemporary medium that she’d not tried her hand at earlier, working closely with a team of animators. Tucked away in one corner of the exhibition hall, are mesmerizing animated video films (see clips given below) where the paintings come alive and take on an altogether new dimension.

This review has attempted to delve into Rokeya’s personal inner world that propelled her to create her art while tracing her trajectory, constantly exploring but never straying away from the themes she chose to work with. The works are an eclectic mix of pictorial diaries, chronicles, fantasy, mythology and a visual assertion of women’s rights in a patriarchal society. Successfully straddling diverse mediums, her works demonstrate her comfort with them, be they black-and-white prints or lyrical paintings rendered in lush, warm colours and muted tones. Over four decades of engaging with art, the accomplished artist created a rich tapestry of imaginative and emotive works with a child-like innocence and a deep sensibility of her chosen subjects.

Curatorial team for the exhibition: Najmun Nahar, Curator; Tanzim Wahab, Chief Curator, Bengal Arts Programme; Ina Puri, Curatorial Advisor

The exhibition at Lalit Kala Akademi, Rabindra Bhavan, New Delhi will remain open till 26 June 2022 after which it will travel to Rabindranath Tagore Centre ICCR, Kolkata, from 7 to 20 July.

(All images are courtesy of Rokeya Sultana and Bengal Foundation unless otherwise stated.)

Ranjan Kaul is an artist, art writer, author and Founding Partner of artamour.

His art can be viewed on his insta handle, @ranjan_creates.

nicely articulated